Worth The Wait

By Bev Schellenberg

It’s taken a long time for my two children to meet my family: 13 years and 10 years respectively. That’s because my family’s been dead that long. My mother and brother died when I was pregnant with my eldest child, my 13-year old daughter. Years before that, my father died of cancer. It’s taken a long time for my two children to meet my family: 13 years and 10 years respectively. That’s because my family’s been dead that long. My mother and brother died when I was pregnant with my eldest child, my 13-year old daughter. Years before that, my father died of cancer.

For two evenings my children spend time with my family as we sit at our dining room table. “Here’s a picture of my mother and father when they were young,” I explain as I take the old black and white photos from the envelope.

These are what remain from my life with the family who raised me: stacks and stacks of mostly untitled photos that span 50 years, many years that I wasn’t alive. For years I’ve dreaded going through the pictures, afraid I’d remember what I wanted to forget, or perhaps that I’d forgotten what I’d hoped to remember, and have no one to ask. But now it’s time to sort, to accept and to embrace the past.

“They look so happy,” notes my daughter as she gazes into the faces of the grandparents she’s never met, unless you count the times we’ve visited their graves in Victoria, on the hill overlooking the valley.

She’s right: I rarely remember my parents looking radiant.

My son comments, “Your dad looks so young, like someone in a show.”

I think about what shows we’ve been most recently watching that exist in black and white: “Like Twilight Zone?”

“Yeah!” my son replies, staring at the picture of my father in his gas mask, standing by the army tank.

I realize my son is meeting his grandparents in backwards order. Most people meet their family and see them grow older as the years pass. For my son, however, through pictures he’s seeing my father grow up, in one picture, at around 10 years of age, the same age as my son, standing with crows on each of his outstretched arms. Then Father and my brother, years before I arrived in the family, standing side-by-side, man and boy with shoulders back, chins raised, smiling and strong. Next Father as I remember him, puttering away in his workshop, tools in hand, building. In several of the photos spanning the years he feeds his beloved birds, his favourite creatures, or he stands with his cherished model planes. I realize my son is meeting his grandparents in backwards order. Most people meet their family and see them grow older as the years pass. For my son, however, through pictures he’s seeing my father grow up, in one picture, at around 10 years of age, the same age as my son, standing with crows on each of his outstretched arms. Then Father and my brother, years before I arrived in the family, standing side-by-side, man and boy with shoulders back, chins raised, smiling and strong. Next Father as I remember him, puttering away in his workshop, tools in hand, building. In several of the photos spanning the years he feeds his beloved birds, his favourite creatures, or he stands with his cherished model planes.

Father’s last photo makes me cry. He sits in his salmon-coloured rocking chair, with a family friend and Mother nearby. I remember that last summer I saw him, when that picture was taken. Father told me he wasn’t going to fight the prostate cancer that had returned a second time, that he was ready to let go. That visit was the only time, before or since, I saw a snake slither along the concrete driveway of our family home, and somehow I knew it would be the last time I saw Father alive.

The first evening of our tour through time, my daughter and I look through shoebox after shoebox of photos, while my son takes breaks between my reminiscing to play video games. By the second night, my son is snuggled next to me, watching more and more memories emerge. Here are several pictures of a young couple, his late grandparents, gradually growing together, with their son, my brother, Brian, soon smiling his way onto the scene. We see Brian grow from inside our very pregnant Mother, to a boy glowing beside his new bike, to trips of Mother, her mother, and Brian off at North American places that I can’t identify, to the yellow, crinkled newspaper article of a happy boy clutching a clarinet, to a shot-gun wedding, into visits at our family home. The pictures change into more colourful memories once I was adopted into the family, thanks to the invention of colour photography. There’s even a birth announcement, declaring the addition of adopted me to the family, 3 weeks after my birth.

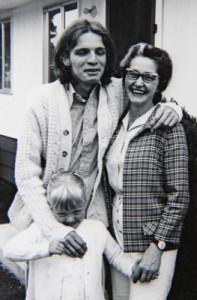

My memories now add to the images and I try to fill in the blank spaces for my children. There’s my grandmother’s aunt, the one who taught me how strong perfume can be worn, modeled beehive hair, long shiny nails and sent us pistachio nuts every year.  There’s Terry and Bruce, the two young men Mother decided to take home with her and me, her 3-year old daughter. Mother took a risk: we met the two men at an evangelical revival meeting in Centennial Park in Victoria. Mother offered them supper, and we drove them to our home in the cherry-red Dodge—hippies who smelled of sandalwood and had lots of hair. The outcome of Mother’s kindness was worth the risk, at a time when “stranger danger” had no meaning. Terry and Bruce became like brothers to me, and Terry is the reason I know about Don Cherry, Tiger Williams, and what the inside of a jail looks like. Over the years we knew Terry, Mother and I visited jail several times when he ended up there. Visiting opened my eyes to the humanness of good people who sometimes make bad choices. There’s Terry and Bruce, the two young men Mother decided to take home with her and me, her 3-year old daughter. Mother took a risk: we met the two men at an evangelical revival meeting in Centennial Park in Victoria. Mother offered them supper, and we drove them to our home in the cherry-red Dodge—hippies who smelled of sandalwood and had lots of hair. The outcome of Mother’s kindness was worth the risk, at a time when “stranger danger” had no meaning. Terry and Bruce became like brothers to me, and Terry is the reason I know about Don Cherry, Tiger Williams, and what the inside of a jail looks like. Over the years we knew Terry, Mother and I visited jail several times when he ended up there. Visiting opened my eyes to the humanness of good people who sometimes make bad choices.

Our relationship with Bruce, the other man we met when I was 3, taught me what faith in a higher power can do. Due to too many drugs, he jumped out a window, thinking he could fly. In consequence to that incident and also through drug use, he ended up with brain damage. However, after making a personal commitment to God, he chose to stop taking drugs and instead to retrain his brain, gradually working from an elementary level of intellect through high school, and finally completing a college degree. He eventually married a woman with two growing children, just prior to succumbing to cancer due to his exposure to asbestos as a young man.

As my children and I continue to look through the photos, some people I can’t identify and unfortunately few of the pictures are labeled, but common elements I recognize: the house my father made and I grew up in on Balfour Street in Victoria, the maturing images of my parents, and the parade of Miniature Dachshunds that arrived in our family even before my brother. As my children and I continue to look through the photos, some people I can’t identify and unfortunately few of the pictures are labeled, but common elements I recognize: the house my father made and I grew up in on Balfour Street in Victoria, the maturing images of my parents, and the parade of Miniature Dachshunds that arrived in our family even before my brother.

I start laughing. On the back of a photo of a typical looking family who I don’t recognize, are the words: “–, the one who cut off Mother’s fingers.” I wonder which mother that caption refers to: my mother and grandmother had all their fingers by the time I came on the scene. But there’s no one for me to ask.

Just over 13 years ago my brother committed suicide and then, a few months later, my mother died of a stroke. My father died years before, and that was the end of our family. Gone. What remains are the memories I’ve carried around with me in cardboard boxes, boxes I left unopened when my now 13-year old daughter appeared , 6-and-a-half weeks earlier than her due date. The pictures remained, sealed in their boxes when my son arrived a few years later. Boxes I carted with me once I separated and divorced from my husband.

Nearing the end of a night of photo perusal, my son has another computer game break. My daughter and I keep sorting through the pictures. I say to my daughter, “Wouldn’t it be great if we find a million dollars with a note that says, ‘For you, Beverley, because I love you. Love, Mother’”?

We chuckle. “It’d be even better if it had your name, and then said it was $2500 for you to get to go on the Japanese Exchange,” I add. My daughter’s wanted to go to Japan for years, and next year is her chance.

“Now that’d be freaky,” replies my daughter, and my skin tingles at the thought. That kind of connection to my departed parents reminds me of the first day my son and I spent in the hospital when he was born 4 weeks early. That night I dreamed my mother and father walked in our hospital room, hand in hand. Walking silently to his incubator by my bed, they leaned over and looked at him, then turned and smiled at me. Then they were gone. Although they’d already passed years before, their visit that night remains with me today as clearly as the memory of an actual event.

My daughter and I keep sorting through a mismatch of my brother’s photos of him holding his clarinet, his daughter in the swing, my childhood friends sitting in the yellow wheelbarrow with me, a glimpse of Mother’s life in a one-year diary. Suddenly, from one of the envelopes I pull out a plastic bag, with something wrapped carefully in paper. Unwrapping the contents, I reveal 5 crisp one dollar bills from 1973. There’s no note, but looking at those carefully wrapped dollar bills, to me it feels like Mother just gave the three of us a note of her love that spans the 13 years she’s been gone.

I pat Charlie, our miniature weiner dog, who’s asleep in my lap. I smile at my daughter, curled up in Father’s rocking chair and my son, sitting nearby. Yes, it’s taken me 13 years to go through these pictures, but it was worth the wait. Before, the contents of the boxes represented what I’d lost, and I couldn’t deal with being reminded of the pain. I see the contents also show what I have: memories of parents that loved me, history that is part of me. Now is the time to share my past with my present so it can infuse my future.

Postscript:

After my father died, I inherited several working model airplanes that he’d made as well as a model of a truck and a police motorcycle. My children have seen these and we’ve talked about who made them. The glass-cased truck and motorcycle stand proudly in our kitchen as a constant reminder of Father’s passion and talent.

In my son’s elementary class, the teacher schedules a block of time each week for a different child to show and share something from his or her life that is significant. In September my son asked, “Is it okay if I bring a model that your dad made?” and I said it was. My son found it challenging to share in front of the class so the teacher booked him for May. Inside, even as I burst with pride at the thought of my son sharing about my father, I wondered what he’d say about this grandfather he’d never physically met. Once we shared the pictures of Father, I knew my son had a strong background into his grandfather’s love of planes and talents with making models, but I still wasn’t sure what he’d say.

Finally his day arrived. We gently windexed the glass case of the truck, and cleaned the delicate exterior on the plane. Carefully, we carried them into the van and then into the classroom. He added the 1958 Plymouth Belvedere car model still in progress that we’d worked on the past summer.

On our way to school, he asked, “What should I call your dad—‘Grandpa’? But some of my friends know “grandpa” and he’s Dad’s dad. I could call him ‘my mom’s dad’ or ‘my dead grandpa’.” I said whatever he wanted to call him was fine with me because it had been 17 years since my father died and I would be okay with whatever he called him.

After my son set up the truck, the airplane and his car on the trolley in the front of the classroom, his peers filed in, some pausing to admire the models. As my son stood in front of his class that day and I sat in the back, watching, he began, “These are the models that my grandpa, my mom’s dad, made.” He proceeded to explain about model building. At some point one boy asked if this grandpa still made models, and my son said, “No. He’s dead.” The boy nodded. His grandpa had died only days before. After my son set up the truck, the airplane and his car on the trolley in the front of the classroom, his peers filed in, some pausing to admire the models. As my son stood in front of his class that day and I sat in the back, watching, he began, “These are the models that my grandpa, my mom’s dad, made.” He proceeded to explain about model building. At some point one boy asked if this grandpa still made models, and my son said, “No. He’s dead.” The boy nodded. His grandpa had died only days before.

I snapped another picture. I will always remember the day I had the privilege of hearing my son share some of his heritage with his classmates. But it’s always nice to have a photo.

Back to Stories

|

June 15th, 2011 @ 10:00 am

Thank you for sharing your story.